home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

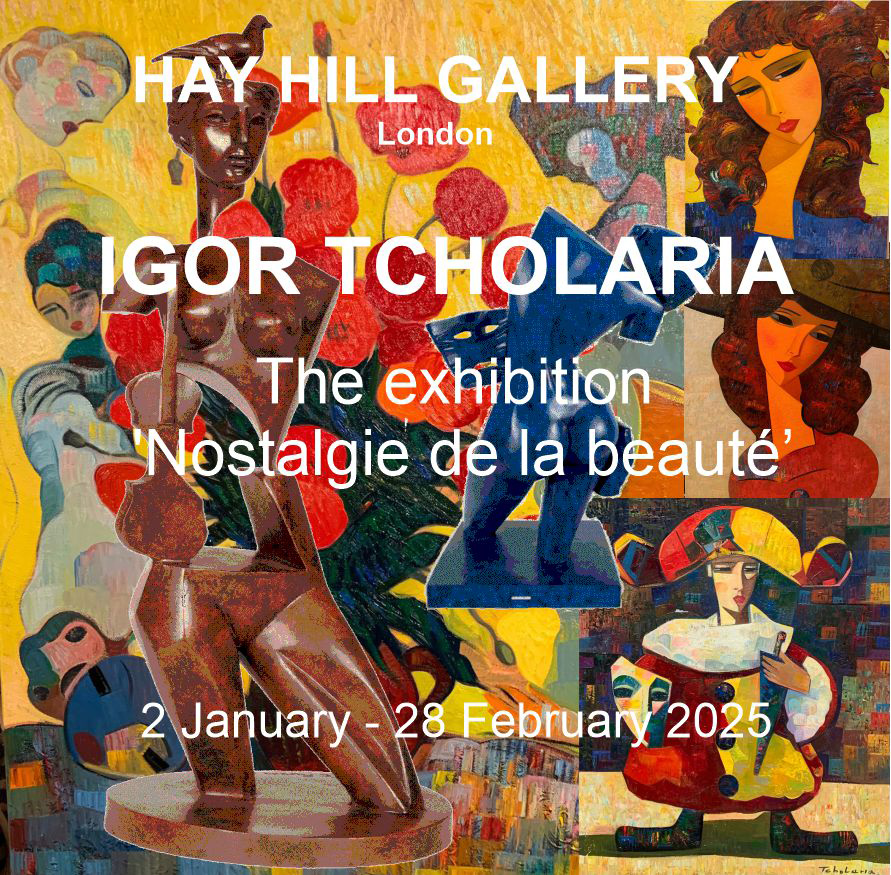

The Artist Statement The Georgian artist Igor Tcholaria lived and worked in Belgium for many years. He collaborated with major galleries in Belgium, Holland, England, Luxembourg, and the United States of America. He participated in dozens of general and personal exhibitions around the world. The work of the Georgian artist is characterized by a combination of an ultra-modern approach to painting with a deep understanding of the techniques and traditions of old European masters. The motifs of the French avant-garde and impressionist artists of the early twentieth century are not alien to him. Igor Tcholaria attaches great importance to the preliminary processing of the canvas. The pictorial layers of the lining often represent independent works of abstract painting in the spirit of Cezanne's layers, Pollack's multi-vector tricks, and Rothko's warm and mysterious halftones. Thanks to this work, a kind of artist's know-how, Tcholaria's canvases live, breathe and supply the owner with positive energy, so necessary for a human being in our turbulent and difficult times. True avant-garde is archaic - Tcholaria claims. It is not for nothing that Pablo Picasso turned to prehistoric examples of cave paintings in search of forms. Igor Tcholaria also adheres to the glorious tradition. In his improvisations, he masterfully maintains a high note of inspiring nostalgia. No matter how sophisticated the inventors of various concepts are, painting is the result of an impressive combination of forms and colours. Let us not forget that having created a world of incredible complexity, the Lord laconically limited himself to two words of commentary. IT IS GOOD - said God.

BIOGRAPHY Igor Tcholaria

This is the ceremony where the president of Russian Academy of Art gives to Igor Tcholaria the diploma of the honour membership in the Academy.

Igor's works are in the collections of Anthony Hopkins, Madonna, John Galliano, Gérard Depardieu, Pierre Richard, Luciano Pavarotti, cruise liner the Queen Mary 2, Volvo company, Philips company, and many other collectors from all over the world.

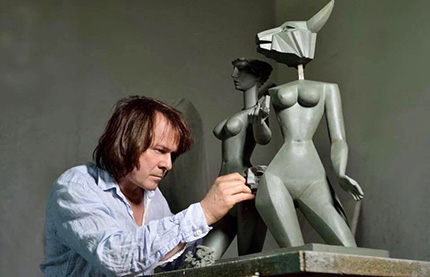

Taming the Chaos Igor Tcholaria calls his artistic method “retro-perspective” (not to be confused with retrospective). In essence, this means that he moves forward in his creative work from the depths of time, mastery and tradition. Like an athlete who steps back to take a running start before jumping. The kinetic energy of this running start can be extremely great. All that remains is to land on one’s feet. Tcholaria feels confident in his flights, even on the quaky ground of contemporary art. He’s resolutely prepared to weed its tangled thickets, accustomed like a true knight to his palette-knife sword and Cubist-form armour. And fairly recently (stepping back to the Bronze Age for his running start?) he turned to what was a new genre for him: bronze sculpture. Combining a classic approach with the vivid forms of sensual improvisations, he managed in a single stroke to create a whole line of original sculptures that have already won popularity in Europe. Tcholaria was born in the town of Ochamchira, Abkhazia, on the Black Sea coast. He received his initial training at the Sukhumi School of Art, where talented pedagogues taught him the basics of the craft and instilled in him a love for painting. Then he continued his education in Leningrad, at the Vera Mukhina School and Academy of Fine Arts. His work is largely influenced by the French Impressionists along with Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Paul Gauguin. Interacting with each other in the artist’s internal crucible, their creative methods were synthesized into a new quality that became the signature Tcholaria style. In addition, he’s spent years experimenting with the texture of the paint layer, striving for a powerful matte finish instead of glossy garishness. During his student years the works of old European masters had an enormous influence on Tcholaria, who spent much time studying and copying them in the State Hermitage and the Old Russian Paintings Department of the Russian Museum. At the same time, he led the life of a typical informal artist, with all the delights and travails of a semi-underground existence. In the mid-1980s Tcholaria was one of the first to begin earning a living drawing portraits of passersby on the street. At that time in the Soviet Union this occupation was not entirely without risk. Once an observant policeman caught him at work in the square in front of Kazan Cathedral. But the vigilant artist noticed the danger in time. Quickly throwing his brushes into his painter’s case, Tcholaria left the girl he was painting to pose in loneliness and disappeared into the cathedral’s colonnade. The law-enforcement officer wandered among the massive columns for a long time to no avail: you can’t catch artists in a maze, for they feel the rhythms of lines better than others. This feeling of rhythm is a manifestation of Tcholaria’s subtle musicality. Whether calibrating combinations of warm and cool tones, like Cézanne, or painting a broken line with a vibrating hand, like Modigliani, the maestro remains invariably himself. He’s on a first-name basis with these great names, whose ghosts quietly hover over his canvases like spirits in a spiritualist séance. Tcholaria’s female portraits are worthy of special mention. His heroines are funny, mysterious, sly and reckless. At times exotic in an Oriental way. At times colourful and monumental. Clearly, the artist does not always require live models. Images constantly flicker through his soul, like evening fireflies in a Black Sea park. Though Tcholaria often deals with the circus theme, he doesn’t depict scenes in the ring; instead, his attention is drawn to the individual characters. Looking at his paintings, one feels the metaphysical longing of Picasso’s harlequins and at the same time their attempt to escape its grip. The artist seems to soothe his protagonists: “You’re colourful and clever. What do you have to be sad about?” One of his works is entitled Look at Me, Look at Me. A harlequin suddenly flies onto the scene and freezes in mid-air. Like a dolphin jumping out of the water. Or a sail floating over the ocean’s surface. Contrasting icily with the dancer are the melancholy girl present in the image and a blue surrealistic figure in the background. This is like counterpoint in music, when a contrasting tonality emphasizes the beauty of the main theme. No wonder the artist repeatedly admits that he prefers working mainly to classical music. He’s especially inspired by Antonio Vivaldi and Johann Sebastian Bach. For Tcholaria, the idea of taming chaos, which he creates on the canvas using an original technique of abstract underpainting, functions as a sort of generator of striking and unpredictable compositions. At first the artist doesn’t restrain his energy in any way. But at a certain moment he suddenly “chokes his own melody” and gazes at the composition like an ancient shepherd at the starry sky, in which not only Big and Little Dippers appear as if on an abstract canvas, but also wild rams, hunting dogs and other phantoms of the imagination. For all its apparent simplicity, this method requires an ideal sense of colour, outstanding plastic abilities and a highly developed intuition, which allow the artist to discern a metaphysical element in random combinations of coloured patches. When Tcholaria first found himself in Europe, it was just this method of spontaneous insight that allowed him to astonish the European public. Throughout the ensuing years the artist developed and improved his trademark technique. Working in this manner, he never knows exactly how the final result will look. And this is the most important thing in art. Surprise yourself, and you’re sure to surprise the viewer. Even God, according to the Bible, couldn’t hide His amazement after creating the Earth. Once Tcholaria became the involuntary coauthor of a hot trend in the fashion industry. John Galliano acquired one of Igor’s paintings, a variation on his beloved theme commonly entitled General. Somewhat later the artist witnessed a showing of one of the designer’s collections, whose main silhouette in many ways replicated the outlines of his general. Igor took no offence. On the contrary, he was pleased. He realized he’d foreseen a major fashion trend, been on the same wavelength as a celebrated fashion designer. It was probably this shared intuition that led Galliano to acquire Tcholaria’s painting in the first place. Perhaps he did borrow Igor’s visual ideas in his work. But after all, Tcholaria himself synthesized his oeuvre from the ideas of the great French Modernists, who were inspired in turn by primordial African masks and Oriental themes. A traveller’s biography is made up of conquered mountain peaks, lakes, seas, oceans and African deserts. A scientist’s activity consists of discoveries and inventions. A poet mostly records marvellous moments, stringing them onto stanzas and constructing his own imaginary life in this way. A professional artist’s career can be visualized by studying the list of group or solo exhibitions he’s participated in. Since year and venue are indicated in the list, you can thus discover the history and geography of his movements. Looking at Tcholaria’s exhibition roster, we see immediately that his home bases and main places of work are Belgium and Holland. However, England, Italy, France, Luxembourg and the US occupy a worthy place in the registry too. Whilst an explorer leaves his mark on a mountaintop, on the North or South Pole, or at the bottom of the ocean, an artist is commemorated by the people who hold his pictures in their collections. In addition to the aforementioned Galliano, these include the singer Madonna; the late tenor Luciano Pavarotti; actors Pierre Richard, Gérard Depardieu and Anthony Hopkins; hockey player Alexander Mogilny; numerous politicians and businessmen; and most importantly, true lovers of art in all countries and continents. The World of Tcholaria For an artist living at the turn of the millennium, the art of both bygone and modern times is as much an objective reality as the earth, sky and faces of surrounding people. The iconosphere, our visual memory, the “musée imaginaire” of which Malraux wrote – it’s unthinkable for an artist to be free of these things, for such freedom can easily turn into professional deprivation and ignorance. The famous philosopher Eugenio d’Ors justifiably considered everything devoid of tradition to be plagiarism. In other words, artists who are ignorant of their roots, or attempt to hide them, can hardly lay claim to originality. Igor Tcholaria maintains an open dialogue with art, and his oeuvre exists in a creative space whose visual world is clearly and precisely demarcated. From a young age he’s been captivated by Picasso, though he loves – and most importantly understands – Paul Cézanne, James Ensor, Amedeo Modigliani and Henri Matisse as well. The paintings Tcholaria creates are not imitations; rather, his art is that of a new reality, one that changed completely after the great Spaniard entered it. Joan Miró once confessed that he was fortunate to be able to create in the same world as Picasso. Such sentiments are probably familiar to Igor Tcholaria too. His characters are seen through his own eyes but undeniably through Pablo Picasso’s “magic crystal” as well, with its perception of reality “from the inside out”, its free juxtapositions of different points of view, its depiction of the known and perceived rather than the visible, and its ability to aestheticize emotional discord and the twilight depths of the subconscious. Honoré Daumier maintained that an artist is obliged to belong to his time, and the apparent insouciance of Igor Tcholaria’s paintings doesn’t challenge that thesis in the slightest. However, the modernity of his art consists neither in showing us shards of a “devil’s mirror”, nor in eschatological motives, nor most certainly in any collection of fashionable devices used to force entry into today’s artistic “mainstream”. No, his art is modern because of its ability to resonate with today’s cultural codes whilst preserving its own intonation. Both semantic and visual. Tcholaria doesn’t avert his eyes from the tragedy of existence. But in his variations, which involuntarily bring to mind his deeply revered James Ensor, he peers at the flickering shadows of life like Cabiria in the final scene of Fellini’s eponymous film, seeking and finding in them both poignance and joy. In Tcholaria’s paintings even tragedy retains the flavour of a game or carnival, where the truth hides behind elegant masks and fanciful costumes. Only here the main role is played not by fabric, by clothing, but rather by luxuriant painterly texture, brilliant visual techniques and resonant colour combinations. Tcholaria’s paintings, along with wisdom about the complexity of art and the modern world, are filled with a cheerful, life-giving force, a sense of the invincible beauty of existence. The most common trap for young and ambitious artists is imitation. Especially if they’re little concerned with the inner substance of their art. But when artists have something to say, it’s easier for them to master not only their visual tools but everything they consciously or unconsciously borrow from the existing iconosphere. The content of Tcholaria’s art is positive, filled with vitality, energy and joy. That holds true both for his early works – sultry decorative landscapes splendidly embedded in their canvas surfaces – and for the later portraits that seem to combine reminiscences of Modigliani’s sitters with the fleeting elusiveness of anxious contemporary faces. The latter are more forceful and dramatic: their fiery chromatic effect and juxtaposition of different viewpoints (The Woman with a Yellow Bird, 2003) seems to reveal the subjects’ characters at different moments in time. Even more lapidary is Woman in a Red Hat (2002), a painting that goes beyond live portraiture to produce a non-figurative impression, revealing the model’s essence in an original way, like an accompaniment. As Ignacio Zuloaga noted, “Art must be vital and free, and under no circumstance the slave of reality.” Tcholaria, despite his cheerful openness to the world, is not as simple an artist as he might seem. His universe, like any carnival, hides behind its masks, exotic costumes and whirling farandoles a certain alarming subtext, a hidden Hoffmannesque element. And only his generous wealth of powerful colour combinations and elastic, seemingly dancing lines – “the substance of art”, in a word – is able to quell the anxiety that arises from the subtle ambiguity with which every work by Igor Tcholaria is deliberately infused.

Mikhail German,

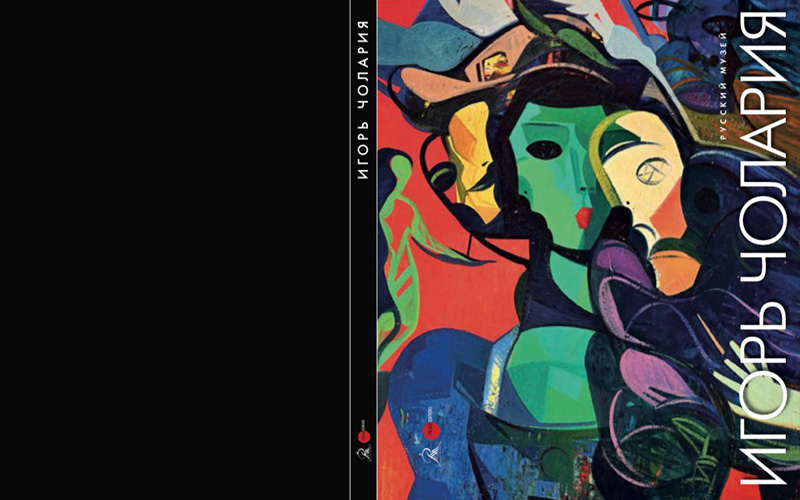

“Returning to the past, I move forward.” - Artist Igor Tcholaria Igor Tcholaria has a studio at the famous 10 Pushkinskaya Street in St Petersburg, a former squat occupied by artists back in the perestroika years. These representatives of the “other” culture existing in parallel to the officially approved one were often referred to as Nonconformists. They rejected the principles of creative life that existed in their country, orienting themselves towards the global artistic process they longed to participate in. Tcholaria belonged neither to their ranks nor to those of the officially recognized painters of the time. A non-revolutionary by nature, he wished only to be an artist, not to repudiate anything. Perhaps this is why he met with such success in foreign galleries, where he chanced to be exhibited, noticed and singled out from among other street portraitists from Leningrad, soon to be renamed St Petersburg. At that time, in 1987, he and his comrades were among the first creators of our country’s own “Montmartre”. Later, towards the beginning of the 2000s decade, he returned to the cultural environment of Russia’s second capital with the rich experience of foreign creative work behind him. “Holland, Belgium, London, Monaco – in these countries and cities there’s great interest in art in every home,” the artist observes. The galleries he worked with then, and continues to collaborate with today, allow him complete creative freedom. Tcholaria strives to stay in the mainstream of contemporary Russian art, defining his creative method by the term “retro-perspective” and adhering to the credo “Returning to the past, I move forward.” In this connection, it’s telling that the artist bought back a number of his works from their Dutch owners to modify and improve decades after their creation. But the essence of Tcholaria’s credo lies elsewhere: in the formal structure of his works and his passion for avant-garde art. “I adore the great art of the early 20th century,” he confesses. Captivated by turn-of-the-20th-century French art at the beginning of his career, Igor Tcholaria began painting landscapes in the French Impressionist style. Later he made a careful study of the Post-Impressionist masters. It seems that his beloved themes of the theatre, circus, commedia dell’arte and equilibrists were largely influenced by the “French” spirit too, for by the 20th century the “comedy of masks” had extended its influence both to French art (here we must mention Pablo Picasso, whom Tcholaria reveres) and Russian culture of the Silver Age. The theatre, circus and itinerant life: this is a logical collection of themes for a well-travelled artist. In addition, the theatre and circus are attractive for their multicoloured variety, transformations and unending motion. This is Tcholaria’s creative oxygen, his native element. However, the artist treats these themes in a melancholy rather than phantasmagorical vein. It’s no accident that his pensive, seemingly inquisitive figures are often accompanied by masks (held in their hands, appearing to hover nearby, and so forth), which play a significant role in Tcholaria’s world. His most recent mask-portraits bear the tragic imprint of Filonov’s Heads, though in the context of Tcholaria’s oeuvre they also express the element of sensuality found in his multi-figure compositions. Flowers, women and dolls are also favourite themes for the artist. On the one hand, women resembling flowers, or women with flowers. On the other, the image of the doll, which like the mask represents the dark side of feminine nature, its tendency to devolve into a marionette in rapacious hands. The portraits of women, even those with specific names, exhibit a conventionality of feature, a visual generalization. Dazzlingly beautiful, they occupy a place alongside the female images of such artists as Amedeo Modigliani or, in particular, Lado Gudiashvili, who wrote: “Woman is the source of life and goodness, … the crowning glory of nature and embodiment of its inexhaustible abundance.” Of the aforementioned painters Tcholaria rates Modigliani the highest, together with Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse. “We must never forget the classics,” the artist declares. Female images are present in almost all of Tcholaria’s works, dictating their will in some strange way, taking the helm of world governance, or assisting in recreating the world from chaos. The latter role is especially pronounced in the artist’s multi-figure compositions from the last decade, which he paints in multiple layers over several sessions. Having invented his own priming method, he’s convinced that paintings should be saturated visually as well, so that one can “read” a plot in their forms, lines, fanciful contours and luxuriant colours. “There’s structure present even in apparent chaos,” Tcholaria explains, describing the synthesis of abstraction and figurality in his works, some of which are exquisitely textured, others, on the contrary, flat and pointedly decorative. In his paintings-narratives he combines texture and laconic patches of colour, later adding smaller details. The world that arises in them is bright and variegated, rich with colour and eddying forms. Encoding “reflections on the realities of life”, in the artist’s words, it contains in its formal structure echoes and reminiscences of various languages of avant-garde art. In their time, each of the classic artists of the international avant-garde spoke in their own language, and each wove their own original artistic fabric that entered the history of art as a unique visual unit for future generations of painters. Tcholaria’s method, which has evolved over the years, uses aesthetic material from the past and organizes pictorial space via a montage technique the artist calls “combinatorics”. However, this organisation is preceded by the chaos of spontaneous abstract improvisation, often using the methods of Jackson Pollock, only after which does work with semi-figurative forms begin. Multiple layers of coloured priming also contribute to the effect of form arising from chaos. While focusing intently on avant-garde art – so close to us and yet so distant in time, already a classic for today’s generations – Igor Tcholaria nonetheless remains a free artist who pays tribute to the joy of creativity and regularly pokes fun at himself. His work eludes precise definition: Postmodernist? Quite possibly. Neo-Eclectic? Neo-Mannerist? In the end, he’s just an artist who can’t imagine himself in another role. Tcholaria’s artistic credo is perhaps most personally reflected in the unexpectedly minimalist work entitled Flowers of Malevich. In the mysterious abyss of a black square sunken into the canvas’ woven fabric flashes of colour shimmer – brightly, triumphantly, yet with an odd kind of humility. Painting lives on. The Cover of Russian Museum Catalogue 2022 of Works by Igor Tcholaria

Catalogue from the Russian Museum (issuu) Catalogue from the Russian Museum (pdf)

Opening ceremony of Igor Tcholaria's exhibition "Taming Chaos" in the Marble Palace of the Russian Museum. September 22, 2022.

Interview with Igor Tcholaria. Exhibition "Taming Chaos". Russian Museum, Marble Palace.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

E-mail: info@hayhillgallery.com |

||||||||||||||||||||